|

This story has been archived from the September, 2002 Trail Runner

Matt Carpenter: The Man and the MountainFifteen years into his phenomenal running career, Matt Carpenter has come to a crossroads.

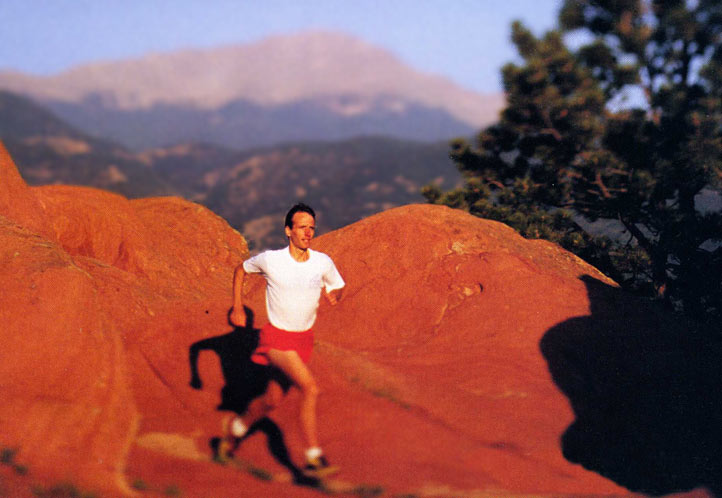

By Brian Metzler Matt Carpenter walks to the sliding glass door in the living room, looks skyward and pauses. He bought this townhouse in Manitou Springs, Colorado, a few years ago specifically because it had a view of his favorite mountain. Pikes Peak is out there somewhere, but today is murky with nothing to see but fog. Perhaps no one is more familiar than Carpenter with the well-worn Barr Trail that winds to the 14,115- summit. He has made a career running that trail for the past 10 years, becoming likely the best high-altitude runner the world has ever known. But now he’s come to a fork in the trail. One path involves a new direction in life, dedicating time to be with his family and accepting the adventures that come with that terrain. The other route, the one with which he is more familiar, includes the challenge of trying to maintain his career as a competitive distance runner. Can he possibly take both paths simultaneously? Carpenter admits it’s unlikely. He turned 38 in July, about the same time he and his wife, Yvonne, welcomed their daughter, Kyla Anne, into the world. An those who know Carpenter realize that moving on with anything but an obsessive, single-minded approach to running may just not be an option.

Although his wiry, 125-pound frame appears as fit as ever, his speed has waned slightly (by his own admission), his hair has started to gray, and nagging injuries are taking longer to heal. “When you’re running fast, you thing, “I’m not going to get old, I’m not going to slow down,’” he says. “And now here I am at 38, and I think, ‘How did I ever run that fast?’”

Rare air He holds course records for numerous mountain races around the world, including the Pikes Peak Ascent (13.3 miles) and Pikes Peak Marathon (26.2 miles). He’s won many of the top (sub-ultra distance) mountain races in the U.S. multiple times and is the only American to run under 60 minutes in New Hampshire’s 7.6-mile Mount Washington Hill Climb. Some of his efforts border on the unthinkable, especially two of his high-altitude marathon marks. In 1995, he won the Everest Sky-Marathon in 3:22:25 — at 17,060 feet, above sea level. Three years later, he won the same race on a different course, at 14,435 feet, in a lung-burning 2:52:57, a time that remains the official world marathon altitude record. Feats like those have earned him the nickname of “The Lung,” among others. “He’s the king,” concedes Dave Mackey, a champion trail marathoner from Boulder, Colorado. “He’s in a class all by himself.” But it’s not only his extraordinary physical talent that sets Carpenter apart. Sure, he has an astonishing resting pulse rate of 36 beats per minute; in 1992 he recorded an astronomically high VO2 max — a measure of the body’s ability to efficiently deliver oxygen to the muscles. His 90.2 mark is the second-highest ever recorded (only a Swedish cross-country skier posted a better mark) and approximately twice that of an average recreational athlete. That alone might have won him a horde of races, but it has been his fanatical training regimen and notoriously stringent lifestyle that has led him to lofty heights. Some of his peers say that since the late 1980s Carpenter has trained with the desperate hunger and extreme focus more typically found in deprived athletes of third-world nations who are trying to outrun poverty.

Frugal fanatic For 15 years, he has eaten little more than pasta, cereal, tuna, and fruits and vegetables — mostly because he can’t rationalize the cost of junk food, soft drinks, and other so-called delicacies. He’s worked as a freelance website developer for the past several years, and puts most of his earnings in the bank. Sure, he has his vices and eccentricities — like mini pizzas on occasion, big helpings of ice cream after races and the $10,000 treadmill in the garage — but for the most part, he’s a minimalist.

“I think he could live on about $5000 a year,” Yvonne says. “He’s very frugal. But that’s how he lives his life. For him, it’s about sacrificing everything else that might get in the way of his running.” A native of Mississippi, Carpenter first began training at altitude when he moved to Vail, Colorado, in 1986. There he found trail races, cycling time trials, and mountain-biking events, not to mention a bevy of endurance fiends to help test his mettle at 8500 feet and above. “He’s been focused 365 days a year for as long as I’ve known him,” says world-champion adventure racer and mountain biker Mike Kloser, who has lived in Vail since the early 1980s. “Taking a day off isn’t in his vocabulary. That’s incredible.” Carpenter hasn’t missed a single day of running in more than five years and only a handful in the last decade. He supplements his outdoor running with high-energy stints on the treadmill twice a week. While he relentlessly trains through illness and injuries, he isn’t always harsh to his body. He takes a lot of naps, usually without an alarm clock so his body can rest and recover as long as it needs to. “I don’t care what you do or how you train. You just have to have consistency,” he says. “These things became habit to me, and I haven’t bothered to change, even though I don’t have to count every penny to the level I once did. Besides, it worked, so why change?”

Ch-ch-changes To no one’s surprise, Carpenter was the first to return, with a comfortable buffer over runner-up Mackey. After boycotting the races in 1999 and 2000, to protest a decision made in 1997 to eliminate money and perks that attract deep, talented fields, he returned last year to prove a point. He became the first person to win the Pikes Peak Ascent and Marathon races on back-to-back days, though his marathon time on Sunday (3:53:54) was the third-slowest winning time in the previous 35 years. He made his point, but did anybody notice? The race still filled out weeks in advance and no one seemed to care that he won each race by more than six minutes, something that never would have happened if a deep field of top-end runners were there to challenge him. Others, however, have stayed away for the same reasons he did. For years, Carpenter has bemoaned the fact that many trail races, including the Pikes Peak races, have eliminated prize money, dropped course-record bonuses, and cut special treatment for elite athletes. Gradually, he says, race directors have become more interested in reaching their events’ participant capacities than staging epic competitions for runners at the front of the pack.

“My personal opinion is that [six years ago when Pikes Peak changed its policy] is when the sport started to turn,” he says, frustration in his voice. “When they realized they could fill the races, a lot of race directors became lazy. The race directors are at the point now where they think, ‘The race fills, therefore we are a success.’ But that’s bad for the sport.” How bad? Take the Pikes Peak Ascent and Marathon. In 1993, Carpenter set course records for both events — 2:01:06 for the 13.3 miles on the way up and 3:16:39 for the 26.2-mile roundtrip. In the last six years, the winning times have slowed considerably in both races. Danelle Ballengee won four Pikes Peak Marathon women’s titles but made her last appearance in 1997 (the last year of prize money), as did Mexico’s Ricardo Mejia, Carpenter’s chief rival in the 1990s. It’s not that the athletes are money-hungry, Ballengee says, but as full-time professional athletes they need money to support themselves. “It’s not the same race anymore,” she says. “It could be one of the greatest races around, and I would love to do it again. But I prefer to do races where race directors support the athletes and understand that those athletes support the sport. And the bottom line is that I want to run against the best competition possible.” To be fair, Carpenter had the sweetest deal of any trail runner in history from 1993 to 2000 when he plied his trade as a member of the Fila SkyRunners. The handpicked team of high-altitude savages competed in insane hypoxia-inducing events in Tibet, Italy, Kenya, Mexico, Malaysia, and Colorado. Fila paid his travel expenses and race fees, gave him free shoes and apparel, and provided sizable record bonuses. Taken out of context, Carpenter’s comments about race directors can sound a bit egocentric. But he insists he doesn’t care about the money for the sake of getting paid — he just wants to attract as many fast runners as possible. In fact, if prize money is ever reinstated at the Pikes Peak races, he says he’ll donate his share to the Friends of The Peak not-for-profit organization. And to do something to help the cause rather than simply complaining, in 2000 he co-founded the Ban- Trail Mountain Race, a 12-mile event on Pikes Peak that offers a $2000 prize purse. Carpenter says one of his fondest and most inspiring memories of Pikes Peak is the moment in 1989 when Ascent champion Scott Elliott effortlessly sped by him near the top of the mountain. It inspired him to train harder and run faster, something that’s been lacking since the world-class talent there has thinned. “It’s not about making a living, it’s about the future of the sport,” says Carpenter. “If you take out the top level, then the people that would become the next top level don’t get pushed, they don’t have a bar to shoot for. Eventually you wind up with events that become ‘did-a-thons.’”

“I get so upset when I hear people say they don’t care about the top level runners.” he continues, getting more animated. “I ask, ‘So then why do you run the race?’ And they say, ‘Because I want to see the scenery.’... And then I ask, “Then why don’t you run the course on your own some weekend?” And the answer is usually something like, ‘Well, I want to run with people so I can get a faster time.’ Ding, ding, ding! That’s all the guys in the front want, too. We want to run faster, too, but we can’t do it if there is no one around us.” Some of his aggravation comes from his obsession to break the 2-hour barrier in the Ascent. He knows his chance is waning, if not already passed. “When I ran 2:01 I figured I’d have plenty of time to break 2 hours,” he says. “But now I wish I would have run 1:59:59 back then. It was a pretty short window of opportunity, especially because of the changes at the race.”

His own man Take last summer, for example, when Carpenter opted not to accept a spot on the U.S. Mountain Running Team, even though he’d earned an automatic qualifying bid by winning one of the deepest American mountain races of the year: the Barr Trail Mountain Race. Carpenter insists he turned down the opportunity to run in the World Mountain Running Trophy championships in Arte Terme, Italy, because he didn’t think he could help the team in a fast-paced 13k race at relatively low altitudes. Still, some thought it was a blatant snub because of his indifference to USA Track & Field, the sanctioning body of the U.S. Mountain Running Team, over what he saw, until recently, as a lack of support for mountain running. Others figured he didn’t want to risk the same humiliation he suffered at the same event, in Germany, in 2000, when he finished as the fourth American and a very uncharacteristic 63rd overall. Carpenter says he wasn’t excited about going to the world championships, partly because he’d had to pay most of his way to the race in Germany. Despite improvements in recent years, USA Track & Field’s Mountain/Ultra/Trail (MUT) Running Council sorely lacks funds, so it cannot cover all of an athlete’s expenses to international competitions. (Teva signed on as a new sponsor to the U.S. Mountain Running Team and is covering many of its expenses this season.) But council member Dave Dunham, a veteran U.S. Mountain Running Team member, feels the event remains worthwhile as an opportunity to run against some of the best mountain runners in the world, though the races aren’t held in the clouds, Carpenter’s favored arena.

“He’s probably the best high-altitude mountain runner around. I’d like to see him compete against the best mountain runners in the world, but you can’t force someone to go up against the best,” Dunham says with obvious disappointment. The Barr Trail Mountain Race wasn’t a USATF qualifier this year. Instead, it is the only North American stop in the $10,000 SkyRunning World Championships circuit.

Baby makes three “I figured I better get in shape before I run with these guys. I didn’t know if I was fast enough,” says Yvonne, a database administrator for a large company in Colorado Springs who finished the 1995 Pikes Peak Marathon in 7:32:58 hours. “But when a friend and I went there, Matt assured us that as long as we were dedicated, it didn’t matter how fast we were. As soon as I met him, I could sense his self-esteem and his dedication, and that was very attractive to me.” While most people know Carpenter as a training fanatic, she sees, appreciates, and encourages his playful side. In the months before Kyla was born, Matt posted a doctored ultrasound graphic that showed the baby running in her mother’s womb. Matt and Yvonne tied the knot on February 20, 2000, in the only place that seemed fitting — on one of their favorite trails on Pikes Peak. The ceremony included a 6-mile trail run with about 65 members of the Incline Club in tow.

It’s perhaps no surprise that Yvonne’s running has improved leaps and bounds in the last several years. She was the 10th woman to finish the Pikes Peak Marathon in 2001, in a time of 5:28:31. Yvonne has an easy-going nature, and her balance might be the best thing that could have happened to Carpenter. While he doesn’t drive anywhere, she drives a BMW X5 sports utility vehicle (the license plate reads “SKYRUN”). She runs hard, but breaks plenty of the rules that her husband has lived by for more than a decade. “Matt said, ‘I can’t train you because you won’t listen to what I say.’ And he’s right,” she says, smiling. “He wants all or nothing. He wants you to be completely dedicated. I love running, but I don’t want to sacrifice my life for it.” In their spare time, the two have worked together on his highly detailed model train set. And Yvonne tolerates and enjoys Matt’s fascination with Star Wars, which is so strong that if Kyla had been a boy, there’s a good chance his name would have been Luke — as in Luke Skywalker. “One year Matt really wanted a Darth Vader birthday cake,” Yvonne recalls with a laugh. “So I had to drive all around looking for a Darth Vader birthday cake. He’s funny that way.”

Moving on Although Carpenter figures he’ll continue to run the mountain as long as his legs are able to move, he knows his likelihood of breaking the vaunted 2-hour barrier is slim. “I would die for him to do it,” Yvonne says. “But for him to do that would mean he’d have to go back to the basics. He’d have to put running first and put everything else on the side. But if he’s going to do it, he’s going to have to do it soon.” In 1984, Portugal’s Carlos Lopes won the men’s Olympic marathon title at the age of 37. In 1995, Dave Scott placed second in the Hawaii Ironman Triathlon at 40. California’s Tim Twietmeyer and Ann Trason, both over 40, continue to turn heads in the Western States 100. But typically, only a special few endurance athletes are able to hang on to top positions in their late 30s, and even then it’s not for long. Carpenter feels he’s still physically capable of breaking the 2-hour barrier on Pikes Peak, but he doesn’t know if he wants it badly enough anymore. Believe it or not, he’s actually found something more important than running. “I don’t use the word retire — running is something you do for life,” he says. “But I’m definitely getting to the point where I need to decide: ‘Do I want to continue at the level that I’ve maintained all these years?’ And with a family starting, the answer is probably a solid ‘No.’ I want to make my family as much of a priority as my running has been.” Brian Metzler is the founding editor of Trail Runner. |

Back to Bio